Canadian Press

Ukrainian Swedes in Canada.

Gammalsvenskby in the Swedish-Canadian Press 1929-1931.

Per Anders Rudling is a PhD candidate in history at the University of Alberta.

His dissertation focuses on the construction of a Belarusian national identity. Research interests include nationalism, anti-Semitism, diaspora, identity and migration. He has published on ethnic minorities in Ukraine and Canadian immigration. Educated in Uppsala, St Petersburg and San Diego, he teaches Russian history and is the editor of Past Imperfect at the University of Alberta.

In 1782, a group of Estonian Swedes were brought to southern Ukraine by Catherine II. There they set up a village called Gammalsvenskby. In 1929 the overwhelming majority of these Ukrainian Swedes returned to their native land of Sweden, a shocking experience for a community which until that time had lived in cultural isolation in a largely pre-industrial environment. Swedish society was uncertain how to treat the newcomers. Bringing them out of Soviet Ukraine, and back to Sweden had been a triumph for the political conservatives. But once they arrived in Sweden many Gammalsvenskby Swedes were treated with disrespect.

As a result while most of the Gammalsvenskby Swedes decided to stay in Sweden, one group returned to Soviet Ukraine, while another emigrated to Canada, attempting to recreate Gammalsvenskby on the prairies. This is the story of the exodus of the Ukrainian Swedes, as seen through the eyes of the Swedish Canadian Press. In his classic study of the different varieties of European nationalism, Hans Kohn makes a distinction between good democratic/western/civic/liberal nationalism on one hand and bad authoritarian/eastern/ethnic/illiberal nationalism on the other. These two forms of nationalism have their origins in the era of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. While the western form of nationalism grew out of the French revolution, eastern nationalism grew out of the resentment stirred up in many areas under French occupation. In contrast to the situation in France and Britain, nationalism in Central and Eastern Europe developed in areas which often lacked clear geographical borders. In addition, many Eastern European peoples lacked the experience of having states of their own. Therefore they often had difficulties establishing a historical continuity that could legitimize their claims to independence.

Instead, Eastern European nationalisms came to base their concepts of nation on language, custom, ethnicity and blood. German thought had also had a massive influence on the formation on Scandinavian nationalisms. Substantial emigration from Sweden helped fuel a strong nationalist trend within the political right. A sense of confusion and national humiliation followed the dissolution of the union with Norway in 1905. This confusion coincided with concerns over falling birth rates in Sweden. The result was the creation of organizations such as Nationalföreningen mot emigrationen [The National Anti-Emigration League] in 1907, which was aimed at stemming the emigration from Sweden. Another consequence was the appearance of a pan-Swedish macro-nationalism, which transcended Sweden’s political borders. It modeled itself upon the pan-German movement and was oriented towards the Swedish irredenta in Finland and Estonia but also took an interest in the situation of Swedish minorities in North America, South America, South Africa and Australia. Like its pan-German and pan-Finnish counterparts, the pan-Swedish movement based its ideas on race and common nationality. "Like pan-Germanism, pan-Slavism and pan-Finnism, pan-Swedishness was based upon a concept of nationality and race. But here one has to be very careful with classification and conclusions. The same term can have several different meanings. Race in a pan-German context stood for a biological supremacy, which we in retrospect know under its distorted form as the theory of an “Aryan Master Race.” The pan-Slavists talked about race in a non-specific, mystical, and culturally motivated way long before the Russian slavophilism formed its program of political action. The pan-Finnish ideology (frände-folks-ideologin) had components of language, culture and race. However, the pan-Swedish racial thinking was not biological in its nature. It was based upon ideas by (Swedish writer) Viktor Rydberg. Rydberg’s ideas, in turn was a compilation of myths of origin and migration to the Nordic lands. Aryan was at this time a linguistic term, which could be used synonymously with Indo-European. The Germanic people constituted one people [folk], of which the Swedes were a part and the least miscegenated. The pan-Swedish movement found support among the political conservatives in Sweden, but its ideas enjoyed little support in the Swedish irredenta, with the exception of Swedish minority in Estonia, which embraced the pan-Swedish movement "with open arms". The Gammalsvenskby Swedes, the subject of this paper, can be said to have embraced the pan-Swedish message as well. This paper is a study of how the established Swedish-Canadian community reacted to and received the Ukrainian Swedes who arrived in Canada in 1930. It is based on a survey of news articles and material published in the Swedish-Canadian immigrant press on the prairies during the period of the exodus of this group of Swedes from Soviet Ukraine to Sweden and Canada. The Swedish immigration to Canada came later than that to the United States with the result that at the time of the immigration of the Gammalsvenskby people to Canada in 1930 there was still a lively Swedish-language community in the prairie provinces. Although not immediately under the influence of the pan-Swedes, the Swedish-Canadian organs were deeply concerned about the issue of Swedishness and how to best preserve the Swedish language and culture in Canada. This was a new, alien environment, where the pressure to assimilate was strong. The arrival of this little-known group of Ukrainian Swedes in Canada resulted in a meeting of two diasporic communities; but it also meant a meeting of rival concepts of what it meant to be Swedish. Canada in the 1920s was coloured by a different sort of nationalism. Even though at this time there was a clear ethnic dimension to Canadian nationalism, by Kahn’s definitions the Canadian form of nationalism would be largely Western: democratic, civic and political.

Historical background. In her wars with Turkey Catherine II conquered an area known as Novorossiia, or New Russia, in what today is Southern Ukraine.

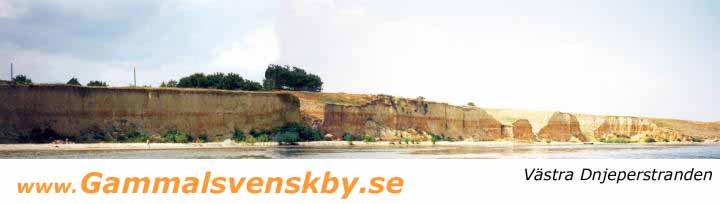

In order to consolidate its claim to this territory, the Russian government encouraged colonization. Many of the colonists were ethnic Germans, a number of whom belonged to various religious sects. The first Germans to settle the area were Hutterites from Austria, who arrived via Transylvania in 1755 and Wallachia in 1767. These groups were followed by 228 families of Mennonites, who arrived in 1787. By 1845 there were about 100,000 Mennonites in the Ekaterinoslav, Kherson, and Tauria guberniias. At the time of the 1897 census there were 378,000 German-speakers living in this area. The imperial authorities regarded them as model farmers and they were widely admired for their efficiency. About the same time an entire Swedish village was brought down to southern Ukraine from Estonia. These Estonian Swedes were descendents of settlers who had crossed the Baltic Sea in the early Middle Ages. This group left the island of Dagö in the fall of 1781. In the spring of 1782, a much-diminished group of settlers arrived on their new lands in the Kherson region. There they set up a Swedish village which came to be known as Gammalsvenskby. In English, Old Swedish Village, in Ukrainian Staroshveds’ka, since 1915 Zmiïvka. The explanations given for the emigration differ, but a combination of intimidation and opportunity seems the likely cause. There was a conflict between the Dagö Swedes and Count Karl Magnus Stenbock, who wanted serfdom extended to the free Swedish peasants. At the same time Grigorij Potemkin, Catherine II’s favourite, offered free land in southern Ukraine. The Swedes made the journey to Ukraine by foot, through the Russian winter. These early Swedish colonists faced a very harsh life, struggling to make a living in a new and unknown environment.

The first years brought incredible hardship to the villagers; between 935 and 1207 people left Dagö in 1781, but only 535 arrived at their final destination in 1782. In March 1783, after various diseases had taken their toll, only 135 people remained, 71 men and 64 women.

To this number, another 31 Swedes, prisoners of war from Gustav III’s war with Russia, were added in 1790. However, the impact of this latter group was marginal. By 1795, only five of these 31 individuals remained.

In Ukraine, the Swedes were joined in 1804 by a group of German colonists. The Germans set up a number of colonies in their immediate neighbourhood, such as the Lutheran Mühlhausendorf (1804), Schlangendorf (1806), and the Catholic Klosterdorf (1805). All in all, in the Kherson area between 1804 and 1883 German colonists founded 41 villages. Some of the Swedes intermarried with their German neighbours, but despite the small size of the group, the Swedes managed to keep their culture and language alive in isolation. Much like their German-speaking neighbors, they were good farmers, and their standard of living was higher than that of the local Slavs.

Lev Trotsky, who himself grew up in the Kherson province, pointed out the sharp differences between the efficiency of the neat German settlements and the rather backward agricultural practices of the local Slavic peasants. The efficiency and relative prosperity of the Germans made many Slavic peasants look at them with envy and perceive them as something of a threat. After the outbreak of World War I, the Russian empire became increasingly nationalized. As national differences were emphasized, Germans were increasingly seen as “aliens” and outsiders.

All German organizations were outlawed, along with all publications in German. Even public conversations in German were banned. Villages and settlements were given Russian names and, beginning in 1915, many Germans were deported to Siberia, the Ural mountains and the Volga region. Imperial Decrees of February 2, 1915, forced farmers in settlements set up by former German, Austrian or Hungarian subjects or by immigrants of German descent in areas adjacent to the western border to register their properties and sell them within six months to two years. This applied to an enormous area stretching 160 kilometers along the border of the Russian empire from Norway all the way down to Persia. Most of the Kherson guberniia was located in this zone, thus these laws applied to the vicinity of Gammalsvenskby. Although the Swedish farms were not expropriated, largely due to the chaos and disintegration of the Russian Empire, it was clear that the political situation was changing rapidly. The relative stability of the nineteenth century was coming to an end. The political situation had become very uncertain.

The collapse of Russia in World War I was followed by a brutal Civil War, when German and Swedish villages were attacked and looted by all sides. Their riches had made them attractive targets: "In the German villages there were more horses and hogs in the barns, more lard and hams in the pantries, more white flour and sunflower oil in their storerooms, more fur coats and carpets in the homes". For long periods during the civil war the front stood along the Dnipro River. Neither the Reds, nor Denikin and Wrangel’s White armies had much love for these settlements of aliens and plundered them freely and with little, if any, risk of being punished. Particularly troublesome for the Gammalsvenskby Swedes were the activities of the green side in the conflict. Svenska Canada-Tidningen specifically mentioned Nestor Makhno’s anarchists, who disproportionately targeted the German settlements in the region. "The poor communities along the river had plenty of experience of all the horrors of war. Especially as a number of loose troop detachments, such as those standing under the command of the famous robber general Macknow [sic] did not behave as regular troops, but rather as—and indeed they were—pure hordes of bandits with murder, plundering and blackmail as their main ambition".

Neither were Gammalsvenskby’s experiences of the provisional government particularly positive. Its weak rulers were unable to stabilize the situation: "When Kerinski came to power it was generally believed that things would get better. But pretty soon it turned out that Kerinski was just another well-meaning talker incapable of initiative or action. Any improvement in the existing poor conditions was impossible. At the so-called elections the people had to vote for the candidates approved by the government. If this was not done you lost your right to vote. It got worse and worse. Children were taken from their parents and put in public kindergartens. If their parents dared to voice opposition, they had their voting privileges taken away. This meant being sentenced to a slow but certain death, since necessities were only handed out to those with ration cards. If one lost the right to vote one also lost the ration cards and therefore any chance of surviving".

World War I, the Civil War and the Sovietization, which began in the late 1920s, meant hard times for the villagers. At the same period, the Soviet policies towards national minorities in the 1920s, meant that the Swedish character of the village was recognized and respected by the Soviet authorities. The Swedes received their own national village soviet in 1926, in which the Swedish language was used. In this early period many of the peasants in Gammalsvenskby were sympathetic to Lenin’s policies. However, this political liberalization was short-lived, and after a few years of relative tranquility in 1928 Stalin initiated his revolution from above.

Agriculture was to be collectivized, five-year plans introduced and society reshaped to its foundations. While the revolutions of 1917 had fundamentally altered the system of government, the Stalinist revolution ten years later affected all aspects of everyday life for the people in the Soviet Union. As Sheila Fitzpatrick puts it: "In the most prosaic terms of everyday life, Russia had been changed by the First Five-Year Plan upheavals in a way that it had not been changed by the earlier revolutionary experience of 1917-1920. In 1924, during the NEP interlude, a Muscovite returning after ten years’ absence could have picked up his city directory (immediately recognizable, because its old design and format had scarcely changed since the prewar years) and still have had a good chance of finding listings for his old doctor, lawyer, and even stockbroker, his favorite confectioner (still discreetly advertising the best imported chocolate), the local tavern and the parish priest, and the firms which had formerly repaired his clocks and supplied him with building materials or cash registers.

***** Continue part 2.

|

|

©2005 Gammalsvenskby Vänner. Alla rättigheter reserverade. Senast uppdaterad: fredag 5 oktober 2007.